- Home

- Andersen Prunty

The Sorrow King Page 2

The Sorrow King Read online

Page 2

The second part . . . He recognized those names. The first three were kids from the high school, fellow students. That wasn’t, however, the only thing linking them. Over the course of the school year, they were the ones who, for whatever reasons, had committed suicide. This was earth shattering news in Gethsemane where there had maybe been one adolescent suicide in the past fifteen years.

And that last name . . . That last name, he didn’t recognize that at all. If this Jeremy character was one of the suicides then surely he would recognize the name. For each of the other suicides, there had been memorials in the gymnasium and public funerals most of the school had attended.

And ‘destroyed’? Why had he written that?

Nearly eighteen and already fucking nuts, he thought, reaching into the desk drawer for the forbidden pack of smokes.

Not in the house. That was his rule. He knew his dad wouldn’t punish him if he caught him smoking. Ever since the death of Steven’s mother he and his dad had been more like friends than father and son but his heart would definitely be broken if he knew Steven smoked and he didn’t think his dad could handle any more heartbreak in this lifetime.

He grabbed the crinkly pack, pulled on a pair of tattered black Converse and a sweater that was wadded up on the floor, half-under his bed, and slipped out of the house.

Slipped out of the house, thinking about the clouds.

He stood there in the doorway, tugging his tattered moss green sweater down over his waist so the chilly air couldn’t snake across his skin. He thought maybe he would just stand there and smoke his cigarette but, looking up at the bloated moon in the cold depths of space, some magic was worked on him and he decided he would go for a stroll around the neighborhood.

Green Heights was the middle-maybe-lower-middle class suburb of Gethsemane. A step up from the apartments sprinkling the outskirts of downtown. A long way from Shade Terrace, the suburb on the other side of Gethsemane. Here, in Green Heights, the cars were American or cheap Japanese, many of them purchased secondhand. If the family unit was intact then the chances were pretty good both parents worked. Most of them worked in retail, middle-management, restaurants, warehouses, or factories.

He liked the little suburb. He liked walking through the neighborhood at night. It filled him with a sense of secret knowledge. The houses all sat quietly, most of the blinds drawn, some of the windows emitting the soft yellow glow of a night owl or the flickering image of a TV most likely left on for comfort more than entertainment.

The chilly air smelled nice. March in Ohio, winter teetering madly on the brink of spring, creating some kind of wild and schizophrenic season that could bring seventy degree balm one day and snow the next. Tonight it was somewhere in between. Just cold enough to be slightly uncomfortable. Just enough warmth in the breeze to remind him that summer wasn’t far away. People had already begun cutting their lawns and that smell was pervasive, along with the clean scent of laundry being dried and blown out of a vent.

He walked slowly along, looking up at the sky. The clouds were milky, swirling around the moon, formless and drifting over a darker sky.

Cumulus, he thought. And then, Jeremy Liven.

Who was he?

Steven didn’t know. He didn’t have a clue. Over the past year, he had taken to thinking about stories. While he never wrote any of them down, he constantly thought of ideas and characters. Maybe Jeremy Liven was a character’s name, waiting to be used.

Or maybe . . .

Maybe Jeremy Liven was the latest suicide.

He dismissed that thought. That was just his mind trying to creep him out.

Far enough away from his house, he stopped and lit the cigarette, pulling smoke into his lungs. It seemed acrid after wandering around in the clean night air but it was the nicotine he wanted. It had a way of perking up his blood and clearing out his head and he thought his head would desperately need some clearing out if he had any hopes whatsoever of going back to sleep later tonight.

First there was the nightmare and then there was the naming of the clouds and then there was the naming of the dead.

And now there was a person walking on the other side of the narrow street.

At first glance, he thought he just imagined the person. Now, looking closer but trying not to stare, he saw that it was a girl. Younger than him, he guessed and, from this distance, very cute. He looked at her just long enough to capture a picture in his head—long straight hair he thought of as reddish but knew could be brown in this light, a bulky gray sweatshirt and jeans that hugged her hips nicely—before looking down at the sidewalk and pretending he didn’t see her.

But not before she had noticed him, not before that brief eye contact that sent his nicotine-infused heart beating even faster.

He resisted the urge to turn and watch her walk the rest of the way down the street, under the lamps where he could see her a little better. That was just his teenage hormones, he figured. Each day was a struggle against the pesky hormones racing through his body, threatening to lift his sex and turn it rigid at the most inopportune times.

Walking with his back to the girl, he wondered why they had both looked away so quickly after spying one another. It seemed like they should have waved or exchanged a knowing nod or struck up a brief conversation. After all, it wasn’t every day he found someone else wandering the streets of Green Heights at two o’clock in the morning.

And who was the girl, anyway? She didn’t look familiar. That must have meant she was either in junior high (which made his restrained ogling seem a little disturbing) or out of school (which made her that much more alluring). Regardless, she took his mind from the other things that haunted him.

Turning the corner, he walked along the north side of the suburb, finishing up his cigarette and looking to his right, where he could see the water tower looming over the park that rested in the middle of the block. The water tower was immense, one of those that was almost as fat at the bottom as it was at the top but not quite. It reminded him of a more angular chef’s hat.

He tossed his cigarette into the street, stealing another glance up at the clouds, thinking about the girl he had just seen and looking forward to crawling back into his warm bed.

The walks always worked.

Lying in bed that night, Steven was totally unaware of the world that was ready to open up for him.

The dream. The clouds. The names of the dead. That was just the beginning.

Three

Good Morning, Death

The pupils of Gethsemane High (or Get High, as some of the wittier stoners were fond of calling it) learned of Jeremy Liven’s death over the morning announcements. The principal, Mr. McFee, unable to shift between emotions with the alacrity of an evening newscaster, came on with the announcement about Jeremy’s death and signed off with a moment of silence. Nothing about the upcoming battles of the baseball or softball teams. Nothing about the lunch menu that day. Nothing about any policy changes or the usual timewasting nonsense that filled the corner loudspeakers in each room.

Steven didn’t know what to think about the announcement.

McFee didn’t say the boy committed suicide but Steven felt that had to be the case. There was a moment, hearing Jeremy’s name, when his heart leapt up into his throat. He found something intrinsically terrifying about writing this boy’s name in his notebook before knowing he was dead, lumping him in with the others who were known to be dead. Yet, there was something about it that was not shocking at all. Steven would have been more shocked if it had been someone else’s name. Somewhere inside, he had known what writing that name meant.

Surrounded by stony silence, he sat in Ms. Hennessy’s first period English class. Jeremy had been in middle school and this was a senior class so it wasn’t like anyone there actually knew Jeremy. Still . . . there was plenty about it to make them collectively uneasy. The fourth suicide of the school year.

Steven wondered how many thirteen-year-olds committed suicide. If a boy that age h

ad that many problems, weren’t those problems usually obliterated by youthful naïveté?

The predominate feeling in the small class of twenty was that of being hunted. Steven could sense a tangible shift.

If something could cause a thirteen-year-old boy to kill himself, then how safe were any of them?

The question did not seem to be, “Would one of them be next?” No, the question on the students’ minds was, “Which one of them would be next?”

So many questions were raised by that fourth suicide. Actually, they weren’t so much raised as strengthened, given a new voice.

Could suicide be some kind of epidemic?

Was it possible to catch the desire to kill yourself?

Who was to blame?

Who was the enemy and who was the victim?

What did it feel like?

Would you get sick?

Would you know you were going to kill yourself?

Ms. Hennessy cleared her throat, bringing the class out of its grim mass reflection.

Steven guessed Ms. Hennessy to be in her mid-thirties. She was attractive in a dark older woman sort of way. While he could imagine many of the teachers as half-witted, giggling cheerleaders in high school, Ms. Hennessy seemed fiercely intelligent. As far as he knew she had never been married. She dressed more fashionably than was usually seen in Gethsemane—especially amongst the faculty. She wore her long dark hair pulled back from her forehead, clipped with a large wooden clasp. Her dark brown eyes made her look perpetually sad. Normally, a bit of shadow beneath them made him imagine she had been awake all night, reading or brooding. This morning, he thought it looked like she had been crying all night. Yes, there was the usual smudgy shadow beneath the eyes but her lids were rimmed with red, too.

She came around to the front of her desk, holding her black coffee mug in her bony right hand, the knuckles red and chapped-looking, her left arm crossed under her small breasts, the hand buried beneath the other arm. The desk dug in just below her buttocks as she leaned against it.

“I think we need to talk about something other than Shakespeare today.”

She sat the mug down on the desk with a dull clunk that resonated amidst the heavy silence of the room. Lowering her head, she raised a hand to wipe away a tear. She sniffed, making a snotty sound. Steven half-expected her to leave the room.

“Is something going on that I don’t know about?”

No one answered her.

“That’s four . . . Four suicides this year in a very small town.” She took a shaky breath. “Let’s start with an easier question. Do these suicides seem odd to anyone else?”

Many students nodded, their eyes open wide. There was a bracing air of hesitation, like they might have to think instead of taking their turn in the game of education. The morning had suddenly turned spooky.

“And when odd things happen, one cannot help but think maybe there’s a reason. Something to unify these relatively bizarre events.”

A dimwitted jock named Aaron Something-or-the-other raised his hand in the second row.

“Let’s not bother with raising our hands today, Aaron. If you have something to say, then say it. This is a free forum. Nothing you say has to leave this room.”

“Well,” Aaron stammered, “it’s just . . . how do you know that it was suicide? They didn’t say it was suicide.”

Ms. Hennessy looked at him like he was stupid. It was a withering look and Steven was glad he was not the recipient. “The ambulance pulled him off a wrought-iron fence that surrounded his house this morning. He had no other marks. Nothing that indicated any kind of struggle. He threw himself from his second-story window.”

“Oh.” Aaron fell quiet.

“What would make a thirteen-year-old boy kill himself?”

“Maybe he was having a hard time at home?” Elizabeth Towson said from just in front of Steven. He found that to be a relatively pat kind of answer, the kind supplied by watching too many heartfelt talk shows.

“Does that warrant killing himself?” She picked up her mug, took a slow sip from it and said, “Because if it does, then I’m sure he’s not the only one. Do any of you feel like you’re having such a hard time at home that you would kill yourself just to get out of it?”

More silence. It seemed ghastly, a little more unfathomable, the way she said it.

“Some people are just wired up wrong,” Elizabeth supplied another fairly obvious answer. Steven wanted to tell her to shut the fuck up. No, he thought. At least she has the guts to try and say something.

“So you’re saying some people are born to commit suicide?”

“Well, not really that . . . It’s just that some people are more depressed than others, I guess.”

“Then how do you know you’re not one of them? How do you know you’re not going to kill yourself next?”

“I’ve never even thought of doing that. I couldn’t.”

“Why couldn’t you?”

“Because I have friends. I like my life. I look forward to my future.”

“And you don’t think Jeremy had any of those things to look forward to? His mother is a professor and his father is a doctor. Do you think that boy did not have a bright future?”

“But money isn’t everything. Rich people get depressed too.”

“But why . . . why wouldn’t he try talking to anyone first? Why wouldn’t a doctor and a psychology professor realize the warning signs?”

“Maybe he didn’t have anyone to talk to? Maybe his parents weren’t home enough to notice?”

“And how sad is that? I guess that’s the point I’m really trying to make. What kind of society are we living in if a child kills himself because he doesn’t understand what is going on around him and doesn’t have a single soul to talk to? If there’s no one who can even tell that a person is suicidal. I mean, that’s a pretty extreme mental state.”

“I think we’re intolerant,” Patrick Sedgewick said from Steven’s left. “It seems like half of ‘society’,” (and here he actually raised both hands and did the index-middle-finger bending motion to denote the quote marks), “understands things like depression and the medication available and the other half thinks all that is just a myth. I would say that, in a place like this, the latter is more predominant.”

“So, you think maybe if he lived somewhere else, in some other town, he would have had someone to talk to? He could have found a way to work through this?”

“Maybe. Who knows? I think people in larger cities understand mental illness better. Who ever really knows why anyone kills themself?”

“I think it’s a cry for attention,” Alison Mobe said from the other side of the class.

“But what good is attention when you’re dead?” Ms. Hennessy turned toward her, trying to drive the question home.

“Maybe he didn’t really mean to kill himself.”

“He jumped from the window of his house toward a spiked iron fence. What about the other three . . . were those also accidents?”

“Well . . . no.”

“Don’t think I’m discounting your opinion, Alison. It’s good you’re saying something. I’m trying to work through a lot of things myself. I’ve just always heard that, was brought up with that being like some catch-all answer for suicide: he was just trying to get attention. I could never really buy into it.”

Now she paced back and forth in front of the class. Steven liked the idea of her trying to bring all this out in the open. With the other deaths, the teachers had merely carried on with their lesson plans in a grimly determined manner. He knew he wouldn’t say anything, wouldn’t lend anything to the discussion—he was much too quiet for that—but he really was very interested in what the other students were saying.

Kate Barrington, a mousy girl who always wore dresses, said, “Suicide’s a sin.”

Another jock, Dave Smoltz, sitting next to Aaron near the front of the class said, “So nothing leaves this room, right?”

“Right,” Ms. Hennessy

nodded.

“Then you want to know what I think about all this suicide stuff?”

“I think we all want to hear what everybody thinks.”

“Fuck ’em.”

Ms. Hennessy nearly lurched backward. “Excuse me,” she said.

“Yeah, fuck ’em. It’s all bullshit anyway. I mean, we all know how it’s gonna go. In a couple days, they’re gonna let us off school early so we can go to this kid’s funeral and we’re supposed to feel so sorry for him because he . . . killed . . . himself. That’s just the same as murder and why should we feel sorry for him if he wasn’t strong enough to get through life. We all have problems.”

Ms. Hennessy was shaking her head back and forth. “You can’t honestly tell me you feel that way.”

“I have a hard time feeling sorry or sad about a person who kills himself. That’s just my opinion.”

“This is a child.”

“It doesn’t matter. He should know better. So that’s why I say fuck ’em all. We don’t need them.” He looked over at his fellow jock, John Skidmore, for support. John was consciously looking away from him, staring at his desk.

Ms. Hennessy’s entire body was now visibly shaking. Her face was an unnatural shade of red.

Dave, who Steven knew didn’t like Ms. Hennessy because, unlike a lot of the other teachers who cared more about seeing the football team win, she made him work and earn his grades, saw how he was getting her worked up.

“And,” he continued, “I feel sorry for teachers who are gonna waste their class time trying to tell us how it’s all our fault or society’s fault . . .”

But Ms. Hennessy cut him off. She closed the few feet between herself and Dave and smacked him in the face. She was bawling now, tears pouring out of her eyes as she smacked him again and again. He lifted his arms to shield the blows.

“People like you are just as sick as people like him,” she spat, continuing to smack about his head. He reached out a huge hand, grabbing the front of her sweater and pulling her into him before shoving her away. The desk bashed her in the hip, her slight frame barely causing it to move. She steadied herself on the desk and looked back, only once, at the class. Steven thought he saw shame written across her face. She smoothed her sweater and his heart hammered as he thought she made eye contact with him. Then she walked out of the classroom.

This Town Needs a Monster

This Town Needs a Monster Irrationalia

Irrationalia Sunruined: Horror Stories

Sunruined: Horror Stories Creep House: Horror Stories

Creep House: Horror Stories Sociopaths In Love

Sociopaths In Love Slag Attack

Slag Attack Pray You Die Alone: Horror Stories

Pray You Die Alone: Horror Stories Satanic Summer

Satanic Summer My Fake War

My Fake War Jack and Mr. Grin

Jack and Mr. Grin The Warm Glow of Happy Homes

The Warm Glow of Happy Homes Fuckness

Fuckness Bury the Children in the Yard: Horror Stories

Bury the Children in the Yard: Horror Stories Failure As a Way of Life

Failure As a Way of Life The Driver's Guide to Hitting Pedestrians

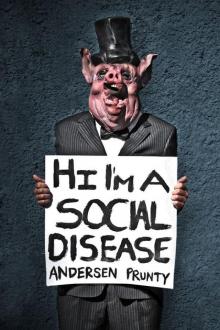

The Driver's Guide to Hitting Pedestrians Hi I'm a Social Disease: Horror Stories

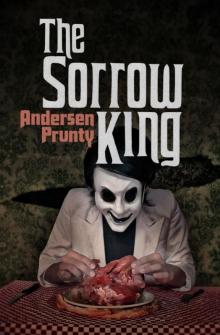

Hi I'm a Social Disease: Horror Stories The Sorrow King

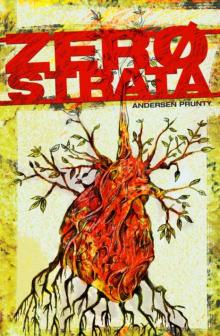

The Sorrow King Zerostrata

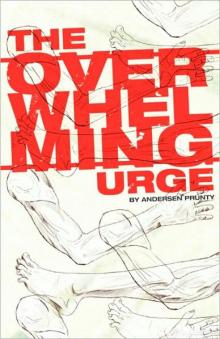

Zerostrata The Overwhelming Urge

The Overwhelming Urge